BEGINNINGS

Had it not been for the German Luftwaffe, I would have been born a Mancunian – as it was, so my Mother told me – that due to a particularly heavy air raid on Manchester late in the evening of 20th October 1943, she and other heavily pregnant women were evacuated from St Mary’s Maternity Hospital, put into ambulances and driven out into the Cheshire countryside towards Prestbury.

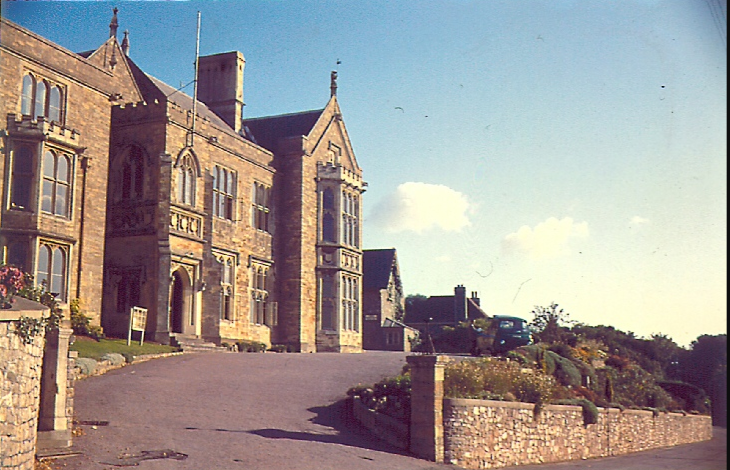

Collar House in Prestbury

Collar House in Prestbury

Sir Oswald Moseley, leader of the British Fascist Party had apparently owned a mansion called “Collar House” in Prestbury, and this had been requisitioned as a maternity hospital – it was here that my Mother was brought just after midnight on Thursday, the 21st October. I was born about 10.30 am that morning – in what had formerly been Sir Oswald’s ballroom.

After about a week in Prestbury, my Mother and I returned to “The Hollies” near Carrington – this was the farm where my Uncle Harry and Aunt Dolly (my Dad’s oldest sister) lived. Mum and Dad had lived at “The Hollies” for about a year since their marriage in Southport.

31st Oct. 1943

31st Oct. 1943

From about 1940, my Dad had been the northern representative for B.A.C. – the Bristol Aeroplane Company – in those days production of various parts of fighter and bomber aircraft were contracted out to engineering companies all over the country – his role was to re-organize continued production in factories that had been blitzed. His work took him north of Coventry and all over the north of England and Scotland. From time to time he would return to the B.A.C. at Filton, Bristol, and stay with Edna – another of his sisters – who lived with her husband first in Bristol, and later in Clevedon.

As the War progressed and air-raid damage to factories involved in aircraft production lessened, Dad was required to spend more and more time at Filton. My Parents decided it would be better to move south permanently.

We moved down to Clevedon early in January 1944, and lived for about a year in a flat in a house called “The Chestnuts” on the corner of Cambridge Road and Kings Road. Mum and Dad were then offered a requisitioned house called “Riverdale” at 76 Old Church Road – we moved there in 1945.

Number 76 Old Church Road, is the first house I remember, it was a large stone-built semi-detached Victorian house with a low walled front garden. A path led down the left side of the house to the enclosed back garden. The dark green front door was off this path and led into the hall with stairs leading upwards, the front room (with bay window) was off to the right. To the left of the hall was the dining room – which led through to the kitchen, where there was a “Belfast” sink with an Ascot over, and beside this was a gas cooker. Outside the back door were a couple of steps down to a brick paved courtyard, where there stood a pump and a large mangle. As you came down the steps from the back door, to your left was a door to the outside loo.

Looking down the back garden, there was a large shed to the right. To the left, a lawn and rockery – beyond which was a soft fruit and vegetable garden and then a rough area right at the bottom. At the very end of the garden was a low stone wall which looked over the meandering Land Yeo River.

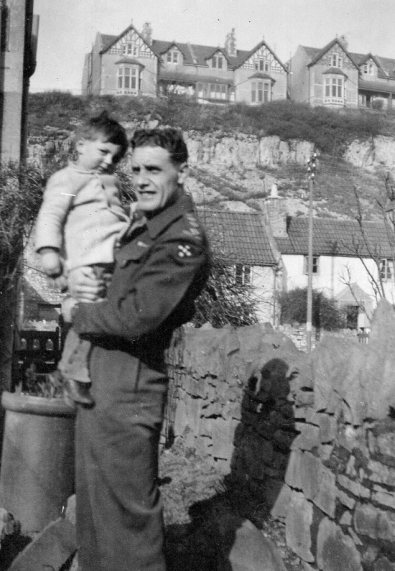

Me and Dad in the back garden of “Riverdale”

Upstairs were two double bedrooms – Mum and Dad’s over the front room, another over the kitchen, and in between, a smaller bedroom (mine), plus a landing with a small adjoining room containing a toilet and washbasin, with a small Ascot over.

Apparently, so my parents told me, it was quite a cold damp house, and whatever the time of year, they often lit a fire in the dining room. Like many older properties, the house had no bathroom and so we, like most people in those days, tended to have a bath just once a week – usually on Sunday evenings. My Mum always insisted that it had to be at least an hour after eating our tea – “to let our food go down.”

On a wall in the brick-paved yard were two large nails upon which hung a large galvanised tin bath (about 4ft 6 inches long) with a handle on each end, and a smaller oval galvanised tin bath (about 2ft 6 inches long) with handles on each end. My parents would carry my bath in first – into the dining room, and put it on the rag-rug in front of the fireplace. If it was cold, then the fire would have been lit. My bath would then be filled, using a white enamel jug, from the Ascot in the kitchen, I would get stripped off and be bathed by my Mum or Dad in front of the fire. After being dried, it was upstairs in pyjamas and dressing-gown – to bed with a bedtime story. After I was dispatched, my bath would be emptied and taken outside and swished round with some clean water before hanging it back on its nail. Then the big bath would be brought into the dining room and placed on the rag-rug in front of the fire. It would be filled from the Ascot and my parents would take it in turns to bathe. After they’d cleared up, the bath would be hung up back in the yard, and the back door locked for the night.

Next door to our house, in what had formerly been a small detached farmhouse, were the Golding Family – Ewart and Alice Golding with their three boys – Ted, Bert and Jack, and their older daughter, Miriam.

The two younger boys (Bert and Jack) used to spend a lot of time with me – sometimes they looked after me when my Mother went shopping and I would help them feed their chickens. If my Mum was agreeable, they would even take me to the Nursery School in Coleridge Vale. The Golding boys had a canoe made from a WW2 aircraft fuel tank – they would often take me – unknown to my Mother – for adventures up and down the Land Yeo.

At the end of the War, Dad transferred to the Planning Department, Technical Division of the newly formed Car Production Division at BAC (Filton) – working six days a week. He went off quite early to work in the morning before I was awake, and returned home at about half-past six in the evening. I remember that on sunny days, I would wait by the front gate for his bus – he would be on the rear platform of the bus, hanging onto the rail. The bus stop was opposite the bottom of Victoria Road – he would drop off as the bus began slowing down, and I would run out of our front gate and up the pavement to meet him.

One of Dad’s best friends at this time was the local policeman – Police Constable Poole. He lived in a police house on the Fernville Estate with his wife and daughter (Joan). P.C. Poole used to take my Dad out hunting rabbits using a ferret and an old jacket – we used to eat a lot of rabbit then. P.C. Poole was also a keen gardener and I remember I used to spend quite a lot of time round at his house “helping” him in his garden.

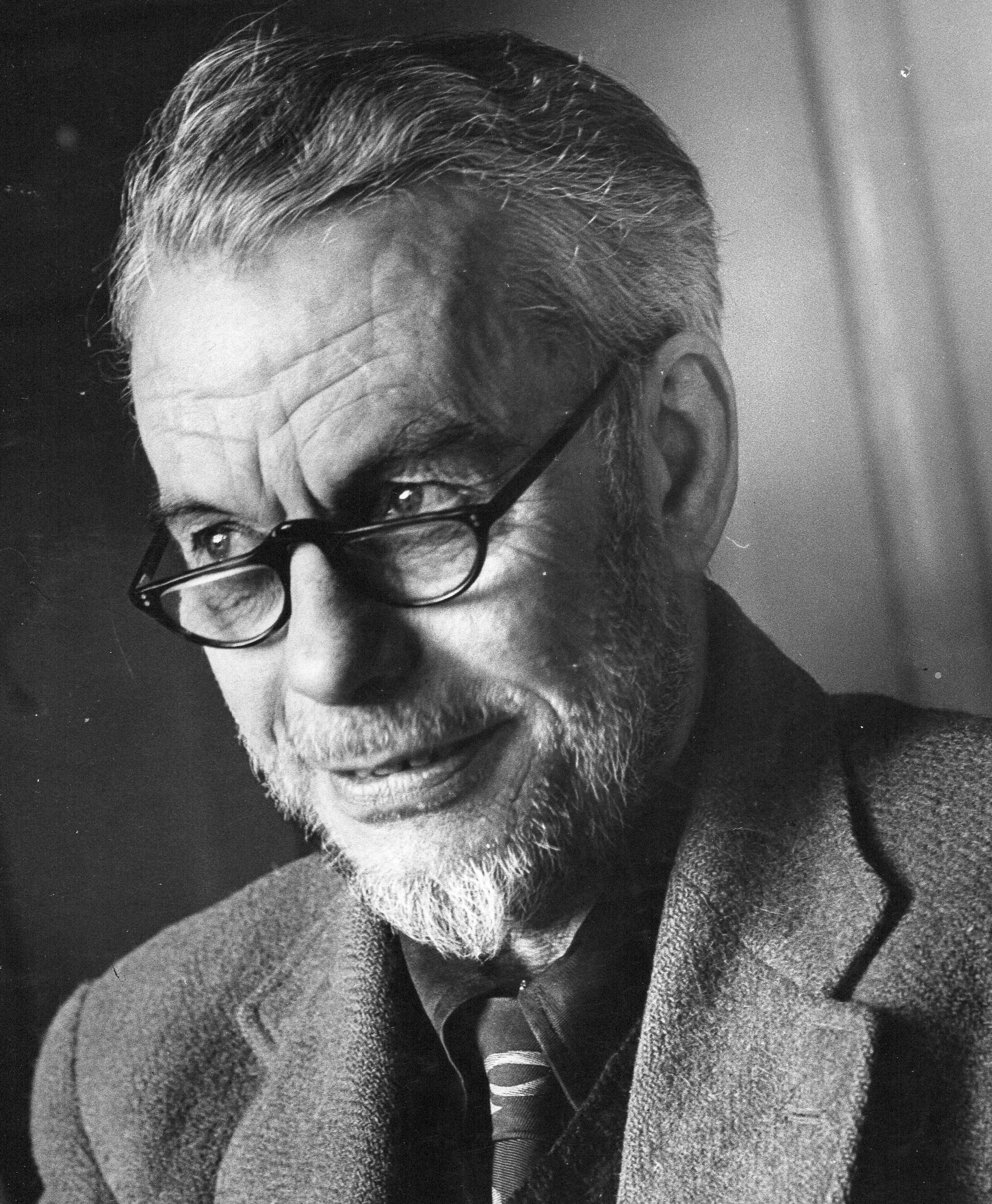

Uncle Charlie

Dad had another friend, who came to stay from time to time – I knew him as “Uncle Charlie.” I believe he had been a commando during the War and he was immensely strong.

One time I recall, when “Uncle Charlie” was staying with us, Charles Heal’s Fun-Fair came to the Salthouse Fields – “Uncle Charlie” and Dad took me. I think it was probably the first time I’d ever been to the fair. There was a “Wall of Death” where motor cyclists rode round the inside of a smooth-sided circular wall about twenty feet high – much to the gasps of the crowd peering over the edge. There were dodgems, roundabouts, coco-nut shies, toffee-apples, shooting gallery, and a boxing booth . . . . . . . . .

Uncle Charlie

Uncle Charlie

The boxing booth was in the centre of a largish marquee, which you paid to enter. Once inside, male members of the crowd were encouraged to strip to the waist, don a pair of boxing gloves and enter the ring to face the “Fairground Champion.” Apparently, if you survived one round – you got 2/6, if you survived two rounds – you got 5/-, and if you survived three rounds – then you got 10/-. If you managed to knockout the “Fairground Champ” – then you got £5.

As we stood there, a steady stream of bruised and bleeding unsuccessful combatants appeared from time to time from the marquee. I remember that “Uncle Charlie” wanted to go in to see what was happening. Dad – as he knew several of the people waiting outside – asked if they minded looking after me for a few minutes whilst he and Charlie went inside. After a few minutes, however, there came the sound of loud cheering from inside the boxing booth – and people outside began pressing forwards towards the entrance to see what was going on inside the marquee. I slipped away from my “minders” and squeezed my way through the entrance towards the boxing ring, just in time to see “Uncle Charlie” pulverising the “Fairground Champ” against the ropes – it didn’t even last one round !! The unconscious “Fairground Champ” was unceremoniously carried from the ring, and, after a lot of arguing, “Uncle Charlie” (who was unmarked) got his £5 prize. It was a proud moment for me to be hoisted up onto his shoulders and carried through the appreciative crowds – he carried me like that, all the way home. Though we visited the fairground a few more times during that week, the Boxing Booth marquee was always closed.

Out and About

Whilst I recall absolutely nothing of the actual War, I do remember the rationing that began in the War, and lasted for a good many years afterwards. I remember that every week or two, I used to go with my Mum to the “White House” in Highdale Road – opposite Christ Church. Here we got my supplies of concentrated orange juice, bottles of cod-liver oil and jars of malt. I – and thousands of other children across the nation – were given daily teaspoons of foul-tasting cod-liver oil, quickly followed by a teaspoon of concentrated orange and then a desert-spoon full of malt. From what I remember, this daily torture went on for many years.

There were no supermarkets during the 1940’s and early 1950’s – we got our groceries from Mr Dyer’s shop in Strode Road, our coal from Victor Peglar – whose yard was on the corner of Coleridge Road and Old Church Road. Our fish came from Mr House – his shop was on the corner of Lower Queens Road. Other shops I knew well were the International Stores – where everything seemed to be wrapped in either blue sugar paper or grease-proof paper – I remember the large square tins of broken biscuits from which I was allowed to take one or two whenever we visited. Parkers sold bread and cakes. We used to get our meat from Hasnip’s (in Station Road) run by Bob Hasnip, his brother Tim and their mother. Our vegetables used to come from Billet’s, and there was Hodder’s the chemist – if we needed medicine.

For special treats I used to go with my Mum at least once a week to the “Golden Slipper” Tea Room (now the Cheung Chaw) – a hundred yards on the right from our house, down Old Church Road. There you could buy cakes over the counter or sit at one of the tables and have a cup of tea and a scone or cake. The waitresses who served at the tables were dressed in black with white frilly aprons and headbands. On sunny days they used to open the French doors onto a narrow grassy strip overlooking the Land Yeo river – the same one that flowed at the bottom of our garden

Another of my favourite haunts, however, was to visit the big shed that housed the town’s steamroller – it was just down the road from my house, to the right of Hangstone Quarry and opposite the entrance to Coleridge Vale Road. The steamroller had been built in about 1929, by John Fowler & Co. of Leeds, with the serial number of 18637. Clevedon Urban District Council had acquired it in about 1931, and when I knew it, it was coloured brown – apparently it still exists today in Devon though it is now painted red.

I loved to be near this mighty traction engine as it snorted smoke from its chimney and hissed with escaping steam. It was lovingly looked after by a couple of roadmen (whose names I’ve long-forgotten), and they took a delight in my interest in their beautiful machine. Whenever I visited them, they would sometimes lift me aboard to look at the furnace. If ever I saw them trundling about Clevedon, I would get a friendly wave and usually a loud blast on their whistle.

Life in Clevedon for a small child in the mid to late 1940’s, was a lot safer than today – in Lower Clevedon, everyone was very friendly and seemed to know everybody else – there was little traffic on the roads and I often used to spend a lot of time wandering about with the Golding boys or with our dog “Butch.”

“Butch” was a funny, rascally character – a Jack Russel terrier who was very loyal and whom, I suppose, for the few years that we had him, was my best friend.

Me and “Butch”

Me and “Butch”

“Butch” was well-known in Lower Clevedon as being a bit of a rascal – Dad and I once witnessed him scampering out of Hasnip’s butcher’s shop with a string of sausages in his mouth, chased by Bob Hasnip, armed with a meat cleaver. Bob never caught “Butch” but I remember him remonstrating with my Dad for having such an uncontrollable dog.

“Butch” and I often went to Clevedon Railway station – where I knew everyone – to watch the steam train going back and forth to Yatton. I used to sit on the edge of the platform, near the buffers, with my legs dangling over, until the train came into view. Then I would go and help collect the tickets from the passengers on their way out of the station. “Butch” got so used to the staff at Clevedon Station, that he often used to go there on his own – and more than once, he jumped aboard the train and travelled on his own to Yatton. After fun and games at Yatton trying to catch him, the staff there would eventually get him back on the train, for the return trip to Clevedon.

Arriving at Clevedon Station from Yatton

Arriving at Clevedon Station from Yatton

Disruption and Change of Scene

In the Autumn of 1946, when I was just three, my Mum contracted tuberculosis – she was in hospital at Frenchay in Bristol for about three months and during that time, I went to stay with my Aunt Edna and Uncle Stuart at “Combe Hay” in Hallam Road. Dad spent his time between work at Bristol Cars, seeing Mum every day for a few hours at Frenchay, and then returning to 76 Old Church Road, to sleep.

My cousin Pat took me “under her wing” whilst I was living with my Aunt Edna – I think my life was so full of interesting things to do, that although I saw my Dad from time to time at weekends, I don’t recall being troubled by the absence of either my Mum or my Dad. Pat, who was about sixteen years older than me, used to push me about in my pushchair all over Clevedon – usually in the company of her many boyfriends – we seemed to spend a lot of time going for walks along the cliff path at Ladye Bay, and visiting secluded spots over the top of Hangstone Quarry or going round Dial Hill.

It was whilst staying at Aunt Edna’s and Uncle Stuart’s, that in the days leading up to Guy Fawkes night, my cousin Stuart – who was about thirteen years of age – decided to make some fireworks. His plan was to make his own gunpowder, put it in cardboard tubes, roll newspaper round the outside and put a twist at one end for the fuse. We were in his Dad’s Victorian greenhouse, and Stuart had already made a number of fireworks a few days earlier, and had them stored in a box on the floor. He was making a second batch and had put all the necessary ingredients for making gunpowder (suphur, saltpetre, charcoal etc) together and was grinding it up with a pestle and mortar. Suddenly, there was a flash – the contents of the mortar ignited – and Stuart dropped the flaming receptacle accidentally into the box of completed fireworks. Within seconds, he and I were fleeing from an exploding greenhouse – Uncle Stuart was not amused with the damage to his greenhouse !

On the night of the 5th November, dressed in warm coats, gloves and scarves and armed with bought fireworks, we carried baking trays full of Aunt Edna’s homemade black treacle toffee – Aunt Edna, Uncle Stuart, my cousins Pat and Stuart, me and my Dad, made our way up the zig-zag to Dial Hill to witness the biggest bonfire and firework display that I’d ever seen.

When Mum came out of hospital, she had to convalesce for anything upto six months. Dad was in the process of leaving Bristol Cars to begin a One-Year Emergency Teacher Training Course at Exmouth, and as Mum wasn’t fit enough to be on her own to look after me, she and I went by train up to Southport, in Lancashire, to be looked after by her Aunts at 143 Duke Street. We were in Southport for about three months, during which time I managed to catch german measles.

Whilst staying with the Aunts, when I wasn’t actually ill, I spent quite a bit of time digging a vast hole at the far end of their back garden – nobody ever came to check on what I was doing. On the day of our departure, I announced to the Aunts what I had been doing over the past weeks and invited them to come and see my handiwork. They were somewhat horrified to see what I had achieved, and I learned later, that they had had to employ a man to fill in the hole. Mum and I returned to Clevedon on the train, and we were soon off again for a week down in Exmouth to see Dad.

It was during this week that we met up with Dad’s new friend, Leslie Colbeck – also training to be a teacher at Rolle College. Leslie’s wife Yvonne, with their daughter, Jeanette, were also visiting Exmouth during the same week. The friendship between our two families was to continue for around ten years with holidays spent together – either them coming to Clevedon or us going to Southampton and Bournmouth – where the Colbeck’s lived.

Jeanette and me on Exmouth Beach

Jeanette and me on Exmouth Beach

EDUCATION, PLAY and OTHER THINGS

Wycliffe School

In early September 1948 I started at Wycliffe School in Linden Road, Clevedon – the Headteacher (Miss Starr) was a formidable lady with steel grey hair drawn back into a bun and a pair of spectacles perched on the end of her nose – she terrified all the younger children and probably many of the older ones too. Wycliffe was a girls’ school that took girls up to the age of about fourteen and boys up to the age of about six.

To begin with, I only went half-days – my Mum used to take me in the morning and collect me at lunchtimes. Just before my fifth birthday in October, I started going full-time to Wycliffe. Mum would collect me and take me home for lunch and afterwards would take me part of the way back – letting me go the rest of the way of my own. For the first few weeks, she would leave me in Linden Road, then after a few more weeks she’d leave me at the end of Princes Road. Mum always came to collect me at the end of the afternoon.

Resplendent in my new Wycliffe uniform

Resplendent in my new Wycliffe uniform

As the distance I was allowed to travel on my own increased, I frequently dawdled on my way back to school in the afternoon and often arrived late. When reprimanded by my teacher (Mrs Harris) for being constantly late – I blamed my Mum for making me help with the washing up after lunch. This excuse worked well for a number of weeks, until unexpectedly (for me), Miss Starr confronted my Mum in the playground after school, to complain that “helping with the washing-up was making me late for afternoon school.” When the truth came out, my Mum began shouting at me in the playground and clouting me around the head in front of lots of amused mothers and rather startled children !

By the start of the Autumn Term 1948, Dad also started his new school – he had been appointed as a teacher at Carlton Park Boys’ Secondary School in Russel Town Avenue, Lawrence Hill, in East Bristol. Initially his responsibility was as form-master of a class of eleven year old boys – teaching general subjects. The Headmaster was a really nice man by the name of Fred Greenland – he was affectionately known as “Pop” by all the boys. He’d been wounded in the First World War and had been Head of Carlton Park for years – and was much loved and respected by practically all of the families in that part of East Bristol.

Dad’s real flair was in Art, and his artistic skills were soon recognised and appreciated by “Pop.” Over the years, Dad developed the Art Education in the school to such a high standard that he was promoted as Head of Art – and in time, was able to take over the vacant Infant School building next door and organise it into a six-room Art Department. During the 1950’s, many of his lads were selected for further commercial art training at the Royal West of England College of Art.

Moving to 48 Westbourne Avenue

Because Mum and Dad had been been living in a requisitioned house in Old Church Road since early in 1945, and the War had been over for two or three years, Clevedon Urban District Council gave them the opportunity of moving to one of the new council houses that were being built on the Westbourne Estate.

I remember going with my parents to look at number 48 Westbourne Avenue – on the corner of Westbourne and Pizey Avenue. As we had no key, we could only look through the ground floor windows – but even on that basis, my Parents agreed to have it. We moved in around Easter 1949.

48 Westbourne Avenue

48 Westbourne Avenue

It was so different from our last house – with a dual-aspect through-lounge with tiled grate and parquet flooring, a small entrance hall, a dining room with built-in cupboards, a solid-fuel Ideal Boiler and a bay window. It had a kitchen with an electric cooker, a Belfast sink with wooden drainer, a walk-in pantry and a walk-in cold-room. It also had a separate utility room with a sink, wash boiler, and airing cupboard containing a hot-tank fitted with an immersion heater. There was a covered outside porch leading to an outside loo and a block-built 15ft x 7ft flat-roofed storage shed (with window) containing a coal bunker in one corner .

Upstairs were two double bedrooms and a single bedroom – all with electric wall heaters and large built-in cupboards for clothes and storage. The bathroom, containing a bath, wash basin and loo, had partial central heating in the form of a heated towel rail taken off the Ideal Boiler which was downstairs in the dining room. At the front of the house was a very small garden, but down the side were two fairly large lawned areas. The 30 ft square back garden was bounded by high walls to the west and east, and the northern boundary was a wire fence which separated us from our neighbours in Pizey Avenue. After what we had experienced in Old Church Road for the last few years, number 48 Westbourne Avenue was a fantastic house

Teacher Training for Mum

By July 1949, Mum had successfully applied for teacher training at Redland College in Bristol. It was a one year course starting on 9th August. During her teacher training, Mum did Teaching Practices at Nailsea and Portishead Secondary Schools. She completed her course and received her Teaching Certificate in August 1950, and began working temporarily in Portishead (Slade Road) from September 1950 to mid 1951.

By late June 1951, Mum desperately needed a more permanent post and I remember going on the bus with her to Bristol and her telling me to stand by the gate at Baptist Mills Secondary (in St Paul’s) whilst she went inside for an interview. She was offered the job to start from the beginning of the Autumn Term 1951.

Friends and Neighbours

Life on the Westbourne Council Estate in the late 1940’s and into the mid-1950’s – from a child’s point of view – was really good – the large areas of grass and the tarmac paths provided many opportunities for child and parent-centred activities. We played football and cricket, and used the tarmac paths as an athletic track. We fished for minnows and sticklebacks in the Land Yeo River near Sidney Keen’s Brickworks in Strode Road, and also fished in the lake – just beyond Westbourne Crescent where the Council were dumping household refuse – the sticklebacks in there were much bigger than you could ever find in the Land Yeo.

We had dens in nearby fields and on Wain’s Hill and Old Church Hill. We roller-skated on the promenade between the Marine Lake and the Pier, we climbed trees in the copse above the Lake and near the swings on the Salthouse Fields and sailed home-made model boats on the Marine Lake. With magnifying glasses, we sometimes lit small fires on Old Church Hill – though once, one of these got out of hand and the Clevedon fire brigade had to come. We looked for and collected .303 brass cartridge cases of bullets fired on the rifle-range out on the sea-wall. We searched for conger eels in the rocks on the foreshore below Old Church and Wain’s Hill, we carved secret symbols and our initials in the bark of trees with our sheath-knives, we dug for treasure and made collections of all manner of strange objects that we found – a much treasured possession of mine was a bag of what we “believed” were emeralds – they were, in fact, decorative green glass pieces from gravestones in St Andrew’s Churchyard.

Whenever the Marine Lake was emptied – in the vain hope of reducing the accumulated mud from the bathing area – we used to search the lake bed near where the paddle boats and rowing boats were for hire in the summer. You could always guarantee, that if you were there searching as soon as the lake was being emptied, you could always find sixpences, shillings, the odd florin or half-crown. Another occasional source of revenue was to be found on the Salthouse Fields immediately after the Fair had left – usually it was only pennies, three-penny bits or sixpences. If however, you wanted a more regular source of income from Easter to the end of the summer holidays, then collecting any empty lemonade bottles along the promenade and taking them back to the many outlets along the length of the sea-front was the thing to do – each bottle had a deposit of between three-pence and sixpence, so you could easily amass enough money to buy yourself some lemonade or an ice-cream with your share of the proceeds.

We played war-games with real tin helmets, gas masks, bayonets and a de-activated hand grenade in a field just off Pizey Avenue, known as the “Donkey Field.” We had “pop” guns that fired corks, cap pistols and potato-guns, as well as water pistols and home-made catapults and bows and arrows – it was a wonder that no one got killed or had their eye poked out !

In 1949, some of the Westbourne Estate was still being constructed – particularly between the electricity sub-station next to 56 Westbourne Avenue and on towards Strode Road – the foundation trenches and stacks of breeze blocks, provided wonderful opportunities for adventures over several weeks. Quite a lot of the houses on the Westbourne Estate were either semi-detached or in blocks of four – we lived in one of the blocks of four. The two end houses (numbers 42 and 48) had external gates to the back garden, whilst the middle two houses had a tunnel or passage to access their back gardens.

Next door to us at number 46, were Bill and Betty Palmer and their son Nicky – Bill worked on the railways. Next to them were the Page Family and next door to them, at number 42, were Norman and Cynthia Wright and their son Barry.

Norman was a very friendly man who would do anything for you – he was a good amateur decorator and I remember him helping Mum and Dad decorate rooms in our house on several occasions during the time we were there. Norman had been in the Gloucester Regiment during the the Second World War and I remember him being called-up again to fight in the Korean War in 1950.

When my Mum started teaching at Baptist Mills Secondary School in Bristol, Cynthia used to come each morning from just before 8.00 am for a couple of hours to clean for my Mum – she also did the washing and ironing and looked after me before I set off for school The cleaning arrangement between my Mum and Cynthia Wright continued for about ten years – long after we had left Westbourne Avenue.

Next to us in Pizey Avenue were Mr and Mrs Belcher – their son, John, was one of my friends – Mr Belcher worked at Wake & Dean Furniture Factory in Yatton. Mrs Belcher used to look after me – after I’d come home from school – until my parents arrived home from Bristol. Next door to them were Mr and Mrs Cooke – Mr Cooke worked on Clevedon Pier and their son, Michael, was also one of my friends. Next door again were the Henley Family – Mr Henley was a cheerful man with a ready smile. He owned a rather large motorbike and sidecar – and from what I remember, he seemed to spend a lot of time tinkering with this machine. Mrs Henley, however, was a rather difficult lady – her feelings towards us depended on how her two children – Paul and Pauline – were being treated by the rest of us.

Me, John, Pauline and Michael

Me, John, Pauline and Michael

In the last of the council houses on that side of Pizey Avenue, were the Davis Family. Mr Davis worked at the Coastguard Signal Station at Walton Bay. Mr and Mrs Davis had two sons – Austin (who was a couple of years older than the rest of us) and Bobby (who was younger than us). We had many adventures with Bobby – many of which usually ended up with him getting wet ! In their back garden, the Davis Family had a large walk-in aviary filled with budgies and canaries. They also kept several large hutches filled with rabbits – which were bred to eat.

Across from us in Pizey Avenue were the Webb Family – from what I remember, they were quite a noisy family – Mrs Web and her daughters always seemed to be shouting at each other about something or other, or Mrs Webb would be out shouting at her son, Colin, or her husband. Mr Webb owned a shooting brake – he often had his head under the bonnet of this vehicle – probably to keep out of the way of his complaining wife. Mr Webb owned the only fish and chip shop in Clevedon, almost opposite the Triangle Clock.

Next to the Webb’s were the Stone Family – John Stone was a really nice man. Before the war, he had worked at the Co-op (on the corner of Station Road and Old Church Road). I believe he had been in Bomber Command and was shot down over the Ardennes and managed to evade capture, and via an escape line managed to get home months later. After the war, he returned to his old job at the Co-op.

John Stone and my Dad became very good friends over the years. They did the Littlewood Football Pools together – hoping to win a fortune – but they never did. John and Norah Stone were frequent visitors to our house in the evening and vice versa. Their son Chris, was my best friend – and it was he, who introduced me to collecting stamps and collecting autographs of sports personalities.

Next to the Stone’s were the Clothier’s – Mr Clothier was a postman and also a special constable. He and his wife had young twins – I’m afraid that Chris and I sometimes used to tease them unmercifully to make them cry.

On the opposite side of Westbourne Avenue from me, were two more of my friends – Terry Short, whose Dad was “the Man from the Pru,” and Jimmy Bridle – he and I often played at stalking wild beasts in the jungle whilst wearing a large fearsome tiger-skin rug that his grandfather had given him.

Round in Westbourne Crescent was one more friend – John Price. He was the son of one of my boyhood football heroes – the great Herbert George “Bert” Price. John and I were the same age and later attended St Andrew’s School and Weston Boys’ Grammar School at the same time.

St. Nicholas School

When my sixth birthday came along in October 1949, arrangements were already in hand for me to move from Wycliffe School to St. Nicholas School in Herbert Road – I moved there in early 1950. My Dad obviously thought that private education was a “good thing” – in reality however, St Nicholas was an awful school. It had about forty-five boys aged from six to about fourteen years run by the Rev. St. Dennis Fry.

There were three permanent staff at St Nicholas – Miss Coulson, Mr “Barney” Barnes (who wore long-johns tucked into his socks), and the Rev. Fry. There were also two part-time teachers – Mr and Mrs Robinson. Tommy Wilkinson – who owned the Oak Room Cafe (above the Maxime Cinema) – used to come in to help with games and P.E. These activities were done mostly in Herbert Gardens or sometimes on the playing field adjacent to the Cricket Ground at Dial Hill.

St Nicholas School in Herbert Gardens 1950 – I’m on the extreme right of the front row. Staff from left to right: Tommy Wilkinson, Mrs Robinson, Mr Robinson, Rev Fry, Mr Barnes and Miss Coulson

St Nicholas School in Herbert Gardens 1950 – I’m on the extreme right of the front row. Staff from left to right: Tommy Wilkinson, Mrs Robinson, Mr Robinson, Rev Fry, Mr Barnes and Miss Coulson

St. Nicholas School had been originally opened by Mr Grundy – a gruff man who wore large brown boots and had his grey hair brushed straight back. He sported a walrus moustache and looked to us, a bit like Joseph Stalin – the then leader of the Soviet Union. When I was at St Nicholas, Mr Grundy would turn up from time to time, and we would all stand reverently as this ogre eyed us up and down. He would perch himself on a chair to one side at the front of the class, tell us to sit down, and then he would stay to listen to what was going on in our lesson. Over the years at St Nicholas, I became a pretty good speller and could draw and paint reasonably well – but I could do very little else.

Boys would begin arriving at school from around 8.30 am – the Rev. Fry slept in a one-roomed flat upstairs and we could often hear him snoring if we arrived early. He would subsequently appear and one of the older boys would collect the Union Jack from inside the school and hoist it up the flagpole at the front of the school. We would all troupe in for morning assembly – held in the front classroom – with Mr Barnes playing the piano. After Assembly we would then return to our classrooms.

My first classteacher at St Nicholas was Miss Coulson – she had about 12 boys in the small room overlooking the back yard. She taught us general subjects up till break-time each day.

Every day there were always two tea monitors in the morning – we all had to take it in turns. As a tea monitor, at about twenty-past ten, we had to go into the small kitchenette that was adjacent to Miss Coulson’s room. We would fill the kettle, light the gas on the stove and put the kettle on – and when it boiled, make tea for each of the teachers. The tea monitors carried the tea to each teacher wherever they were in the school – usually the two downstairs classrooms and one upstairs. Older boys from another class used to carry in the crates of third-pint bottles of milk from the front yard, to just inside the front door. Each boy was expected to collect one bottle of milk each per day from the crate as he went out into the back yard for morning play.

The back yard was actually a hard-packed area of gravel and stone-dust, bordered on one side by a stone wall, and on the other, by a high wire netting fence separating the school yard from next door’s garden. At the far end of the the yard was stone wall, about chest height, with “soldiers” on the top. If you looked over, you found yourself looking down onto the playground of Wycliffe School. It was great sport to hurl bits of gravel over the wall into their playground, and then hide from the girls and their teachers, behind the “soldiers” on top of the wall.

Because of our antics, the Rev. Fry was frequently visited by staff from Wycliffe who complained about our behaviour. We would then all be assembled in the yard to apologise in unison, to the ladies from Wycliffe. However, as soon as the Wycliffe Staff had set off back to their own premises – and the Rev. Fry had gone back inside – we knew we had about four minutes to mount a hail of gravel and other missiles onto the hapless girls before their teachers returned to Wycliffe playground.

When I first went to St Nicholas, some boys went home for dinner. Amazingly, however, all the St Nicholas staff used to depart at dinnertime too – leaving the rest of the boys to their own devices in the empty school. I used to take a packed lunch and there was always much swapping of sandwiches etc. between the boys.

All new boys staying in the school at dinnertime were put through an initiation ceremony by the “old hands.” In the ground-floor front classroom, was a walk-in storage cupboard. Innocent newcomers were shoved into this dark cupboard for a few minutes. Older boys (who had already hidden themselves on the shelves of this cupboard) would bombard you with balls of screwed-up paper and also books – together with high-pitched screams and shouts – all designed to scare the living daylights out of you !

One dinner-time I remember, some older boys began flicking milk from the half-empty milk bottles, at each other – this was soon picked up by more and more boys. The milk residue from the bottom of the bottles soon ran out, so milk bottles were then partially filled with water from the various taps around the school so that the “flicking” game could continue. As one can imagine, it was not long before the stairs, hall, landing and classrooms were swimming in milky water. Realising that there would be trouble, some of the older boys had the bright idea that we should clean it up before the teachers returned after lunch. Mops and rags were located and we all set to work. The results were somewhat patchy and rather unsatisfactory and so someone suggested that better results might be achieved by adding more water and soaking and mopping everything.

When the Rev. Fry and his staff returned after lunch, they found a very wet, but very clean school – and all the boys playing innocently outside in the yard – hoping not to raise any suspicions.

Retribution was swift, long and very hard on the ringleaders – no one was left unpunished – I got an after-school detention. Detentions were recorded in the “Detention Book” together with details of the crimes committed. Details of these misdemeanours would, at the end of each term, accompany the School Report to parents. Many boys had several detentions for this dinner-time escapade, and no doubt fearing further parental retribution at the end of term, it was not surprising therefore, that the “Detention Book” listing all the criminals and their crimes “went missing” just a few days afterwards. The book was recovered a year or two later in the space under the floor of the front ground-floor classroom during some building repair work.

As a result of our lunch-time escapades, the opportunity for bringing packed lunches ceased. All those boys who could go home at lunchtimes had to do so – the rest (and I was one of them) had to pay for lunches at the Oak Room Cafe above the Maxime Cinema, and eat with the Rev. Fry. The Oak Room Cafe was run by Tommy Wilkinson. The cooked two-course lunch cost a shilling – the ten or so of us who stayed for lunch, were escorted down to the Oak Room Cafe by the Rev Fry – but not before he had checked and securely locked the school. After we had eaten and paid for our meal, we were escorted back to school again – in time for the afternoon session.

The Oak Room Cafe as I remember it

The Oak Room Cafe as I remember it

I remember a very sombre lunch at the Oak Room Cafe – it was Wednesday 6th February 1952 – the day on which King George VI died. The radio was switched on, and we, and the other diners, ate our meal in complete silence. The only sound apart from the occasional clinking of cutlery on plates, was the sound of continuous funeral music being played over the radio.

Dead Body

I’m not sure which year it was – it was a Friday in late October in either 1951 or 1952. We had been to the Oak Room Cafe as usual, with the Rev Fry, for one of Tommy Wilkinson’s lunches. As the Half term Holiday was due to start that afternoon, we were dismissed straight after lunch from outside the cinema. As it was my usual habit to wander about here and there – rather than going directly home, I decided that afternoon, to walk along Old Church Road towards the Steamroller shed to see if my friends (the roadmen) were there. As luck would have it, the shed was locked, and peering through the crack between the doors, I could see that the shed was empty. I knew that my two friends were out on the steamroller somewhere in Clevedon.

I decided to make my way up the narrow winding path behind the shed, through a thin copse on the side of Hangstone Quarry, through the bushes at the top, climb over the rustic fence and join the public footpath over the top of the quarry. I then intended to walk down to Victoria Road, along Strode Road and into Westbourne Avenue and home.

I set off up the path leading from behind the steamroller shed, and was soon approaching the bushes near the top – where the path got a bit narrow. I found my way blocked by a figure, lying face downwards away from me. The figure was wearing brown shoes, green trousers and brown tweedy jacket. As we were only about a week away from Bonfire Night, part of me concluded that this was some life-sized Guy Fawkes that had been abandoned or hidden for later use. Unable to get past, I decided that if I wanted to investigate my “Guy” further, then my approach would have to be from the public footpath that led over Hangstone Quarry.

I retraced my steps back down towards the steamroller shed – it was still closed up. There was nobody to be seen as I walked back along Old Church Road and up Hillside Road. I turned into St John’s Avenue and began walking up the winding public footpath until I reached the rustic wooden fencing – over and beyond which, was the narrow path through the bushes to where “Guy” was lying.

By now, I was beginning to have severe doubts as to whether it really was a Guy Fawkes after all – maybe it was someone who wasn’t very well. I’m not sure quite what I was feeling as I climbed over the rustic fence and entered the area of the bushes – but I can remember calling out “Hello” several times. Within a few steps, I came across the figure with the top of his bald head towards me – I couldn’t see his face as he was lying in a pool of blood.

Strangely, I didn’t feel scared by the macabre scene in front of me – I remember turning quietly and making my way back through the bushes to the wooden fence, beyond which was the public footpath. Climbing over, I began walking over the top of Hangstone Quarry. By the time I reached Victoria Road, I had made up my mind that maybe I should tell someone what I had seen – but there was absolutely no one around to tell. I crossed over by the drinking fountain at the bottom of Victoria Road, and began walking up Strode Road towards Westbourne Avenue.

On the corner of Westbourne Avenue and Strode Road, I saw three workmen repairing a stone wall. I had first met them a couple of days earlier, when they had let me spend a few minutes shovelling through their mortar – so they knew me. I stopped for a while to talk with them – though I wasn’t quite sure how to broach the subject of what I had seen, but eventually said “Guess what I’ve found ?”

Various suggestions were made – all of them incorrect. Finally I told them what I’d seen and I remember one of them telling me to “Clear off you little bugger – telling us such stories !” I persisted and eventually one of the men said he would take me down to the Police Station where I could tell them what I had found. Taking me by the hand, we walked down Strode Road into Old Church Road, past my old house and past the cinema towards the Police Station.

Here the workman explained to the sergeant what I had told him. After listening, the sergeant told the workman to go back to work and then turned to me to ask for my version of what had taken place. I relayed my story very carefully, word for word – even telling him exactly what one of the workmen had said to me when I told them what I’d found.

The sergeant called a constable from the back room and quickly explained what was required. The constable put on his helmet and, taking me by the hand, we went through the front door. We crossed over Old Church Road and up Hillside Road and into St John’s Avenue. We made our way up the winding footpath till at last we reached the rustic wooden fence, over which was the narrow path leading through the bushes to “Guy.” The constable told me to stay by the fence, whilst he climbed over and disappeared into the bushes. There was a lot of rustling about and then, a minute or two later, he reappeared and told me to “run along home.”

I set off over Hangstone Quarry for the second time that afternoon and soon reached Victoria Road. I crossed into Strode Road and walked along it towards Westbourne Avenue. The three workmen whom I’d met earlier had packed up and gone home. I turned into Westbourne Avenue, reached number 48, and let myself in – rather than going next door to Mrs Belcher.

Mum and Dad usually arrived home soon after five o’clock. I can remember thinking over the events of the afternoon and wondering quite how I was going to tell them. For some inexplicable reason, I was now beginning to feel a sense of guilt about what had taken place, and by the time they arrived home, I had decided I wasn’t actually going to say anything at all about what had happened. However, not long after they arrived home, there was knock on the front door.

My Dad went to answer it – it was P.C. Poole. For a few minutes, there was the sound of hushed voices coming from the front hall and then the sound of P.C. Poole departing. Dad came in and asked me whether anything had happened on the way home from school – at first, fearing I was in trouble, I assured him that “nothing had happened.” Though with further questioning and encouragement from my Dad, I slowly recounted the afternoon’s happenings to my somewhat astonished parents.

My Dad was, I think, very fearful of the effect might have on me, and decided that the best solution was to have a fish and chip supper from Mr Webb’s shop, followed by a visit to the Maxime Cinema to see the war film “The Frogmen” starring Richard Widmark – it certainly did the trick !!

Going to the Maxime Cinema

The “Maxime” Cinema – more or less the same building that is now called the “Curzon” – is apparently one of the oldest continuously running cinemas in the country – it originally opened just after the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912.

When I lived in Westbourne Avenue, going to the “Maxime” on a Saturday morning, was the highlight of the week for most children aged between about six or seven upwards to about the age of fourteen. What seemed like hundreds of excited youngsters would assemble in a disorderly line along the front of the shops on the ground floor of the cinema building just before 10.00 am on Saturday mornings clutching their sixpence – waiting for the doors to open.

In those days, the foyer was twice as big as now, with the ticket office just to the left at the bottom of the stairs. You had to go up one flight of stairs and turn left through double doors to get to the stalls. The stalls were always filled up first, and it was a question of finding a seat with your friends anywhere you could – seats were all one price. At last the noisy rabble would be seated and the programme would be ready to start – the lights would dim and the show begin.

There was always a western – usually Hopalong Cassidy (William Boyd) with his sidekick “Gabby Hayes,” or a Tom Mix film, or Roy Rodgers and his horse “Trigger.” The “baddies” always wore black stetsons and the good guys always wore white ones. If they weren’t fighting “baddies,” then they were fighting red Indians – we soon learnt that “the only good Injun was a dead Injun !”

Sometimes there were a few Disney cartoons – Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Pluto and Goofy. There was always a comedy film – either Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, or “OId Mother Riley (with Arthur Lucan and Kitty McShane). Sometimes there was a “Batman” or “Zorro” film.

The shouts, cheers, screams and laughter from the audience were often deafening and sometimes objects would be thrown at the screen in support of the heroes in their fight against “the enemy.” Missile throwing usually brought the film to a shuddering halt – the house lights would go on and the Cinema Manager would come on the stage. He would bellow at the miscreants who were out of their seats, he would complain about the missile throwing and, amid raspberries and other indescribable noises, one or two well-known criminals would be threatened with ejection. Once order was re-established, he would then depart – to a mixture of loud cheers, boos and raspberries – the house lights would dim, and to increasing cheers from the young audience, the film reel would stagger to life and the morning’s entertainment continue.

If I remember correctly, the Saturday morning film show would finish at about twelve noon, and within minutes, excited youngsters would spill out of the exit doors on either side of the screen and onto the pavement and wend their way homewards. In our case, my group of friends and I would re-enact the adventures we’d just seen on the silver screen, all the way home. The blue gabardine mackintoshes – widely worn by youngsters in the the late forties and fifties – made admirable cloaks for Batman or Zorro or other caped crusaders swooping along the top of Hangstone Quarry.

For quite a number of years, Mum, Dad and I went out regularly to the Cinema on Friday evenings. I always wanted to go upstairs on the balcony or into one of the boxes at the side – Dad always said that the best place to sit was in the middle of the stalls – whether that was actually true, or whether it was the cost of the seats that appealed – I’m not sure. If my memory serves me well, centre stall seats were 1/6 each (about 7p in today’s money) and my ticket cost ninepence (about 4p).

In those days, there didn’t seem to be much in the way of different categories of films – most films shown at the “Maxime” seemed suitable for children. There were westerns, war films, crime, comedy and romantic films. The sort of films I can remember seeing included: “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon” (western), “Ivanhoe,” “The Mudlark,” “Oliver Twist,” “Destination Moon,” ” The Greatest Show on Earth,” “Bambi” and “Swiss Miss” (Laurel & Hardy). The film performance usually consisted of a “B” film followed by adverts and the Pathe News, followed by the major film. Performances were only from Monday to Saturday and began in the early afternoon, and were repeated until about ten o’clock at night. If you were so inclined, you could actually sit from about 1.30 pm through to the end of the evening without having to pay for a new ticket (over 8 hours). If you were there at the end of the evening’s performance, it was marked by the playing of the National Anthem – at which most people stood reverently until it was over – though there were always some, who would make a bolt for the door as soon as the music began.

As I have said, we used to go regularly to the cinema on Friday evenings. For various reasons, my Mum didn’t always come – it would then be just me and my Dad. I remember one particular Friday – Mum had been unwell and Dad didn’t want to leave her, but she insisted that he and I went as usual. We were about an hour into the performance and were both engrossed in watching an exciting western, when a crudely written message appeared superimposed on the screen. The message stated that we were “required at home immediately” – I can remember my disappointment on having to leave the film at that point, and never knowing how it turned out. Mum had apparently been taken ill at home on her own, and had been able to get help from Betty Palmer (next door). Her husband Bill, had run down to the phone box in Old Church Road (by the Salthouse Fields) and phoned Dr Hylton, and the “Maxime” Cinema.

Our weekly visits to the cinema “tailed off” with the acquisition of a television in late 1952 when the Wenvoe transmitter opened. We did however, go to the cinema from time to time, to see something different. I remember sitting with my parents – all of us wearing red and green lensed-glasses to watch 3D cinema in Bournemouth. I also remember seeing “Cinemascope” for the first time – in a film called “The Robe.”

Car to Pier Beach and Ladye Bay

My Parents had a number of cars over the years. When I was about two or three years of age, Dad had a box-like Austin 12 – which he kept at Mr Ford’s garage on the corner of Strode Road and Old Church Road. As far as I can remember, Dad didn’t have this car long – I think he got rid of it in about 1946 – about the time he transferred to Bristol Cars.

His next car purchase was in about 1950 – it was a two-door, four-seater 1936 Ford 8 with the registration number of AHR 205. Dad bought it from the garage on the Pier Beach,

where there was a Wems Coaches Booking Office, with two petrol pumps on the roadside and where some of their coaches were stored and maintained (now the cafe at No. 5 The Beach). We spent a couple of weekends at the Garage, repainting the car inside and out with black cellulose paint, and Mum made some loose-fitting fawn coloured covers for the “leather” seats – which had seen better days. Dad kept the car in a “lock-up” garage at the back of Willcock’s Garage on the corner of Pizey Avenue and Old Church Road. As well as using it to go to school in Bristol, my parents used to go out for little trips (with me) on Sunday afternoons – usually around the lanes of Kenn, Yatton, Kingston Seymour and the Gordano Valley and along the Coast Road to Portishead. They then became even more adventurous and we were soon visiting Weston (via the Kewstoke Toll Road) and even travelling up in the Mendips – to Burrington and Charterhouse.

Me in the driving seat at Brockley Combe

Me in the driving seat at Brockley Combe

Before car ownership, visits to the Marine Lake happened now and again during the summer, as did visits to Little Harp Bay and the Green Beach – but it was always a bit of a problem on these visits to cope with all the picnic stuff, travel rugs and me.

Now that we had a car – new possibilities opened up – the Pier Beach ! Having a car meant you could take almost everything with you – except the kitchen sink – and spend a whole day on the beach. We became fairly regular visitors to the Pier Beach during that summer, until someone suggested we might like Ladye Bay even better – so we tried it – and that was the start of a long and happy connection with Ladye Bay, that lasted until the beginning of the 1960’s.

Car ownership also opened up the prospect of holidays away from Clevedon – we once stayed with friends in a Tudor manor house – said to be “haunted” – at St Katherine’s (near Bath). One summer, we rented a bungalow near Burton Bradstock in Dorset, and every Whitsun, for about ten years, we rented caravans with uncles, aunts and cousins in Lyme Regis. We visited the Aunts in Southport, and visited friends in Bournemouth, Oxford, London and Tewkesbury.

Within a year or so, Dad got rid of the Ford 8 and bought a 1938 Hillman from Willcocks’ Garage – that was soon followed

Dad and our 1938 Hillman – behind Willcocks Garage

Dad and our 1938 Hillman – behind Willcocks Garage

by a 1954 Hillman Minx with four doors and faux leather seats. His first new car didn’t come until 1963 – an ivory coloured Triumph Herald 12/50

1951 – The Festival of Britain

After the austerity of the war, the Clement Atlee post-war Labour government planned the Festival of Britain as the “tonic to the Nation.” It was not without it’s critics, and many felt the £8 million would have been better spent on housing. For many people in Britain, the world outside the proposed Festival was a grim place – rationing was still in place, dockers were striking, the Korean War was in full swing, the Rosenbergs had been convicted of spying for the Soviet Union, and the testing of nuclear weapons continued apace in Nevada.

In the midst of this grimness however, the Festival of Britain introduced a sense of possibility in the world. It was designed to show what was best about British culture and design – it was to be Britain at its best in terms of both its history, its industrial development and, looking towards the future. It covered aspects of architecture, engineering, science, medicine, history and culture. A huge 27 acre bomb site had been found in London (almost opposite the Houses of Parliament) on the south bank of the River Thames. A range of exhibition buildings and structures were erected, including the Royal Festival Hall (which is all that still remains of the original site), the concrete and aluminium Dome of Discovery (a structure whose diameter of 365 feet and height of 93 feet made it the biggest dome in the world), and the precariously balanced pencil-thin Skylon. The year had also been carefully chosen, as it was the Centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851 – the Festival of Britain opened in May 1951.

1951 Festival of Britain with the Dome of Discovery and Skylon

1951 Festival of Britain with the Dome of Discovery and Skylon

Mum and I travelled up on the train from Clevedon in late June – it was my first visit to London. To experience riding on the Tube, seeing the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace, a boat trip on the Thames and then to visit the Festival site was a truly fantastic experience. The memories of riding on escalators in the Dome of Discovery, marvelling at life-size models of dinosaurs, inspecting jet engines and clambering onto huge railway engines, and standing beneath and looking up at the Skylon – have remained with me ever since. Just as fascinating for me, was the display of allied and captured enemy WW2 planes assembled on Horse Guards Parade – a great day out for any eight year old boy !

Amazingly, the Festival site was controversially flattened when Winston Churchill led the Conservatives back into power in October 1951 – it was as if the vision of the future was somehow out of step with the real world. It is said that almost 8 million people visited the Festival – I’m glad I was one of them.

The Bully

I’ve only been bullied once in my life and that was for a few days when I was eight. It started one day towards the end of the week, as I was walking to school by one of my roundabout routes, through the Fernville Estate. His name was Richard – he was bigger than me and about twelve years of age and went to Highdale Secondary Modern School. It first started with him commenting on my St Nicholas uniform, and then it developed into name calling – on the second day, there was a bit of pushing and shoving. My Dad sensed I was unhappy about something that evening, and on the following day, I feigned illness to avoid going to school.

On the Saturday morning, whilst fiddling about in the shed with some wood, a saw and a hammer and nails, Dad came in and asked me if anything was wrong. At first I was rather reticent, but eventually told him about Richard and about all that had taken place over the previous two days. His solution was simple . . . . . . . . . .

My Dad found a small hessian sack, and getting a few old newspapers, we began screwing up the newspaper sheets into small balls and stuffing them into the sack. When it was full, he securely tied the bulging sack from the roof of the shed. Next he got a sheet of card on which he drew a “life-size” comical face – with a big nose. The face was then fixed to the sack at what I estimated to be the height of Richard’s face. I was then given a few hints on boxing and then left on my own, to punch hell out of “Richard” – especially around the area of the nose. I practised most of the rest of Saturday and quite a lot of Sunday too – I could hit “Richard” squarely on the nose – even with my eyes closed . . . . . .

As you can imagine, I could hardly wait to set off for school on the Monday morning, in the hope of meeting Richard and trying out Dad’s plan. As I approached the area where my foe lived, he suddenly appeared from a nearby gateway and started name-calling. I ignored him at first, and he moved in closer to begin jostling me. With Dad’s advice ringing in my ears, using all the strength I possessed, I gave Richard one huge punch on the nose. His nose literally exploded under the force of the blow – blood spurted out across his face and on my fist. The look of disbelief on his face must have been equalled by my own – he turned and fled home – I turned and ran in the opposite direction – away from any possible terrible retribution from his Mum.

That evening, Dad asked how things had gone and I explained what had happened – he was obviously pleased at the outcome and assured me that Richard wouldn’t bother me again. About an hour later, however, there was a knock at the door – and Dad went to answer it.

Peeping through the net curtains of our front bay window, I could see a lady talking earnestly to my Dad. Standing next to her was a boy with sticking plaster all round the middle of his face – it was Richard. From what was being said, it was obvious that his Mum was demanding to see the thug who had beaten up her son. Slowly, I eased my way out of the dining room and into the hall, and peeped out at her from behind my Dad.

When she saw me and compared my size to that of her son, she immediately turned on him – accusing him of wasting her time. As they walked away from our house, I remember the wonderful sight of Richard being clouted around the head and shoulders by his Mum. Dad was right – Richard never did trouble me again !

Christmas

Ever since I was a little boy, I have always enjoyed the magic of Christmas. I have many happy memories of different Christmases – mostly whilst living at Westbourne Avenue. I think one of my earliest recollections was the Christmas after we moved in, when my Mum and Dad took me to see the pantomime at the Salthouse Pavilion (between Haskell’s “Westend Gift Shop” and the Salthouse Pub) – it was Cinderella. I can remember being invited onto the stage – with two other children – by the Ugly Sisters, to learn and sing and do all the actions to “I’m a little Teapot, Short and stout. Here’s my handle, Here’s my spout.” etc. It was obviously well received by the audience who laughed and cheered as we came off the stage.

In Six Ways in Clevedon, where the “One Stop” shop now is, there used to be a shop called “Babyland.” Each year, on Saturday afternoons from mid-December, “Babyland” used to have Father Christmas – his Grotto was in the basement, and a queue would form at the appointed time, in the adjacent alleyway behind the building, accessed from Alexandra Road. All the Mums and Dads would assemble with their excited offspring as they shuffled their way forwards to rear door of the “Babyland” basement and the entrance to Santa’s Magical Grotto. Sitting on Santa’s knee, he would ask you whether you’d been good all year – your answer would be relayed to Mum or Dad. Then you would tell him what you hoped Santa might be able to bring you on Christmas Eve. I always thought Santa was a little deaf, as he always repeated – more loudly – what you had told him you wanted. Having told your wishes to Santa, you were then allowed to dip into a very large box of wrapped gifts – pink for a girl and blue for a boy. Then you were directed pasts shelves of “goodies” and on upstairs to the ground floor where there were more delights to drool over.

Being so soon after the War, there was not too much choice in the range of toys available – in my letters to Santa (of which I still have several), I always asked for a tangerine, chocolate money and crayons – if I was feeling lucky, I might even ask for a box of dates too. One Christmas, I was delighted to get a “Lone Star” cap pistol – I was the envy of all my friends – it was far better than any toy gun that my friends had ever had.

A few days before visiting Santa’s Grotto, when my Mum used to pick me up from school, I used to find an excuse to divert her in the direction of “Babyland” to look at the displays of toys in their windows. One year, I remember wanting a metal racing track that I had seen in the “Babyland” window – it was a metal figure-of-eight two-lane track with blue and red wind-up metal cars. I knew it was asking a lot to expect Father Christmas to bring such a big present – but he did – though I could never figure out quite how he’d actually got it down our chimney !

One Christmas, two of the Aunties came down from Southport to stay with us in Clevedon. Being Catholic, they decided they wanted to go to Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, at the Catholic Church – just at the top of Marine Parade. Mum, Dad and I went with the Aunts – it was my first time in a Catholic Church, and I remember ducking each time when the priest began swinging burning incense around in the thurible, on a long chain. In those days, the whole service was in Latin and, of course, I couldn’t understand a single word – I thought it very mysterious that the Aunties seemed to know this strange language, and knew exactly what was going on. The service finished just after midnight and I can remember trying to hurry the four of them home as quickly as possible – I was terrified that Father Christmas would arrive in my bedroom, find my bed empty and leave without filling my stocking. I’m pleased to say that he hadn’t, for my stocking was full when I awoke the next morning.

One particular Christmas Eve that I remember, I was particularly excited. I had, as usual, written my letter to Santa and pinned it to my stocking on the bottom of my bed. Once in bed, no matter how I tried, I just couldn’t get to sleep. The more I lay there unable to sleep, the more worried I got, knowing that Father Christmas wouldn’t come if I was still awake.

Eventually, I must have “drifted off” and then awoken again – this time feeling a heavy weight on my feet – maybe Santa had come ! I sat up in bed – it was dark and the room was filled with moonlight. Not wishing to disturb my parents, and having no bedside light, I proceeded to feel what was at the bottom of my bed. Whatever it was, was large and heavy. By the light of the moon, I realised it was a long large dressing gown – and as it was cold, I put it on. I began searching through my stocking – there was a tangerine (which I ate), a bag of chocolate money (which I ate), a box of dates (which I ate), a torch – which I flashed all over the bedroom and then realised I could use it to illuminate the decorating of my new crayoning book with my new packet of crayons. At the bottom of the stocking was a Christmas cracker – which I pulled. So there I was, sitting up in bed, wearing my new dressing-gown with my torch switched “on” (propped on my pillow to shine on my colouring), with a paper hat on my head and blowing the whistle I’d found in the cracker. I was making so much noise and so engrossed in my colouring, that I wasn’t aware that my bedroom door had opened and there stood my Dad. As you can imagine, he wasn’t too happy about having his sleep disturbed. I had to put everything back in the stocking, take off my dressing-gown and put it at the bottom of the bed, settle down and go back to sleep. I had rather a fitful sleep – expecting it to have all been a dreadful dream and that maybe Father Christmas had never called at all – I was woken by Dad the next morning to find it wasn’t a dream after all.

Apart from the year that the Aunts came to stay at Christmas, the three of us always had Christmas Day at home. Christmas Dinner was always roast chicken with all the trimmings, followed by home-made Christmas Pudding – it was always a mystery to me that I always seemed to find the silver three-penny piece in my portion of pudding . Afterwards was spent in front of the fire, roasting a few chestnuts and listening to the radio or, from the time we had acquired a television, watching the entertainment on that.

Car ownership in about 1950, brought about a change in our Christmas celebrations. After we had had our Dinner at home, and everything was cleared up, we used to go off to Uncle Stuart and Aunt Edna’s house in Hallam Road for tea, and to spend the evening with them. I used to enjoy these evenings for it was an opportunity to see my older cousins – Stuart and Pat.

Comics, Papers, Books and Hairdressing

I can never remember learning to read – it just seems to have been something I could always do. Right from an early age, I used to look at newspapers, magazines, comics and books, and ask my parents what particular words were, and then I would remember them afterwards.

Dad used to buy the “Daily Mail” – then a broadsheet – from a shop called “Little’s” (in the Triangle) on his way to work in the morning. In the evenings, after Dad had finished looking at it, I would try to read what it said. I also liked to look at the cartoon strips – “Rip Kirby” (who was a Special Agent) and “Flook” (a rather strange woolly-like creature whose friend was a boy called Rufus).

I can remember sitting at the table in 76 Old Church Road and writing the football results down on Saturday evenings from the radio – in the vain hope that Dad might win the pools. Dad also used to buy either the “Evening Post” or the “Evening World” on his way home from work. On Sunday we had two papers delivered – both are now extinct – the “Sunday Pictorial” and “Reynolds News.”

When Dad was not cutting my hair in the garden (if fine) or in the shed (if wet), he and I used to go to “Coopers” in Coleridge Vale Road North (opposite what is now the Christadelphian Church Hall). Apart from the wonderful smells of the sprays, gels and Brylcreem, there was always a lot of chatter about the successes or failures of various football teams and also much talk about the successes or otherwise of British boxers of the time – such as Don Cockell, Freddie Mills and Tommy Farr. What I enjoyed most at Cooper’s however, were the comics. Mr Cooper had vast collections of “The Beano” and “The Dandy” – he also had “The Victor” – but best of all, he had a regular supply of American Marvel Comics with “Spiderman,” All-Star Comic hero “Superman” and DC Comic hero “Batman.” It was always a great relief to go into Cooper’s and find a long queue, for it meant I could expect to have about half an hour or so, reading his comics.

Seeing how much enjoyment I was getting from Mr Cooper’s comics, Dad used to buy me the occasional “Dandy” or “Beano” – so I could read further about the adventures of Corky the Cat, Lord Snooty, Biffo the Bear, Dennis the Menace and Desperate Dan. When I was about nine, I had my own pocket money of sixpence per week – I could now afford to buy the “Eagle” – it cost me fourpence ha’penny each week and the rest I could spend on sweets.

The “Eagle” was a marvellous comic with science, stories, comic strips and cut-away drawings of cars, planes, ships, tanks, motor bikes etc. My favourite characters in the “Eagle” were Dan Dare (Pilot of the Future, set in the 21st Century), PC49 (adventures of a Metropolitan Police Constable), Jeff Arnold and Riders of the Range, Sergeant Luck of the Foreign Legion, and Jack O’Lantern (about smugglers and highwaymen).

From an early age, I had access to books – though most of them were not children’s books. The earliest children’s book (which I still have), is called “Some Nursery Rhymes” containing three illustrated stories of “Old Dame Trott,” “Sing a Song of Sixpence” and “Jack and Jill.” When I was little older, I was very fond of “Toby Twirl” and the “Rupert Bear” books that I had as presents at Christmas. When I became a fan of the “Eagle,” then the Eagle Annual was always a good present at Christmas – as were the “Riders of the Range” and “PC 49” books issued by the publishers of Eagle.

My bedroom had a small bookcase with lots of Dad’s books on – from quite an early age, I used to try and read books like “Treasure Island,” “Captain Hornblower R.N.,” “Robinson Crusoe,” “The Wind in the Willows,” “Children of the New Forest” and the “Thirty-nine Steps.” I’ve read and enjoyed them all many times since.

The Piano and Television

We often used to travel on the P & A Campbell Steamers from Clevedon Pier – they were quite cheap, often crowded, and ran more frequently than the steamers nowadays. They were big paddle steamers, painted black and pale pink with lots of varnished woodwork

and one or two white funnels – they had names such as the “Bristol Queen,” the “Cardiff Queen” and “Glen Usk.” Sometimes we used to sail to the Old Pier at Weston and stay for the afternoon on Weston sands – an opportunity to ride donkeys and eat ice-cream or candy-floss. Once we went to Penarth and then onto Barry, where there was a huge permanent funfair which included a high helter-skelter.

It was on the boat trip back from Barry that Mum and Dad were approached by a lady who asked if I was their son. When they said that I was, and asked the lady why she wanted to know – she apparently said that she was a music teacher in Bristol and that I had “pianist’s hands.”

In the bow of the “Bristol Queen”

In the bow of the “Bristol Queen”

The conversation developed in such a way, that by the time we arrived back at Clevedon Pier, my parents probably thought that they had a budding piano-playing prodigy on their hands. The outcome was that the following Saturday, Mum, Dad and I went off to Bristol to “Mickleburgh’s” shop in Stoke’s Croft, to look into the possibility of buying a piano.

In those days, the rear of “Mickleburgh’s” shop was a vast museum of different kinds of musical artefacts – there were harpsichords, pipe-organs, fairground organs, hurdy-gurdys, pianolas etc. Mr Mickleburgh (Snr) took great delight in showing and demonstrating his many instruments for us. My parents eventually chose a small modern mahogany-cased piano – which was delivered to Westbourne Avenue the following week. Before its arrival, a piano teacher was engaged – at a fee of three shillings and sixpence an hour – by the name of Victoria Greenhalgh.

She was a matronly spinster in her early sixties with white hair. She was very much into “the Theory and Practice of Pianoforte Playing.” She made me practice scales for most of each lesson with a pencil rubber balanced on the back of both my hands – apparently it was imperative that the backs of the hands were level when playing !

Over the years I was with Miss Greenhalgh, I learned all about brieves, semi-brieves, minims, crotchets, quavers and semi-quavers. I learned all about four-four time and three-four time and took and passed several theory and practical exams – I even played solo before an audience in the Central Hall, in Old Market, Bristol – but I never learnt to sight-read music. For years I struggled through Beethoven, Chopin and other worthy composers, but eventually, Miss Greenhalgh and I parted company – partly because she didn’t want to teach me popular music numbers and partly because I didn’t practice enough. One of the reasons I didn’t practice was because of the sound of the television coming from the next room.

I first saw television in about 1950. One of my best friends at St Nicholas School was Rodney Denmead – his Mum and Dad had a television. Mr Denmead owned a bicycle shop which was next door to a radio/television & electrical shop in The Triangle. On the odd occasion I used to go to Rodney’s for tea, we used to watch the flickering image (looking as if it was through a snowstorm) – transmitted all the way from Sutton Coldfield – on their television.

By late July 1952, my parents decided that they would like to purchase a television, and as the Wenvoe transmitter (near Penarth) was about to open – that settled the matter. Dad went to see Mr Light at “Clevedon Engineering” (opposite W.H. Smith and next to the Land Yeo). Mr Light, I remember, had a huge street-map of Clevedon on the wall of his shop showing all the houses in the town – each house on the map, that had a television supplied by “Clevedon Engineering,” had a coloured flag (mounted on a pin) stuck in it. Ours, I remember, was the third flag on Mr Light’s map. You could only get black and white television then, and there was only one BBC Channel – our television was a 12 inch Bush that cost Dad, 69 Guineas. To begin with, reception was poor, but as soon as Wenvoe opened in August, the picture quality was much improved.

Television programmes were very limited at first – apart from “Watch With Mother” in the early afternoon, programmes tended to start round about 5 o’clock for children. There were long periods of the day when nothing at all was broadcast – just the “test card” was shown – this was apparently to enable television dealers, when installing new sets, to adjust the horizontal/vertical holds and the contrast/brightness controls correctly.

The first continuity announcers that I remember were MacDonald Hobley, Peter Haigh, Mary Malcolm and Sylvia Peters. Among my early favourite children’s shows was a string puppet show called “Muffin the Mule” with Annette Mills. Programmes for grown-ups included “The Brains Trust,” in which a panel of “experts” answered questions sent in by viewers – or “What’s My Line” which was a quiz game, chaired by Eamonn Andrews in which a panel of celebrities had to guess the occupation of contestants from a mime and asking questions – where the answer could only be “Yes” or “No.” If a contestant was able to answer their questions with “No” ten times – then they were a winner. The first soaps I recall were “The Grove Family” and “The Appleyards.”

As television was “live,” there were often intervals in transmission. The BBC would put on “The Interlude” – usually some idyllic country scene like a breeze blowing across a cornfield, or horses pulling a plough up and down a field, or a potter at work, or “Angel Fish” swimming idly round in an aquarium. In the early 1950’s, the television day ended with “The Epilogue” – then the National Anthem would be played and then everything would close down – usually by about half past ten.

Even though many of the programmes were rather “tame” in comparison with today’s television schedules – they seemed infinitely better than the prospect of a half hour’s piano practice on weekday evenings and an hour a day at weekends !